We’ve been here before: The 1918 Influenza Pandemic

Posted June 3, 2020 at 5:53 am by Tim Dustrude

SJI Historical Museum is back with their History Column for June…

Although it’s now been a little over 100 years since the outbreak of the Spanish Flu, many of us grew up hearing a grandparent’s stories of family experiences with the double punch of world war and an influenza pandemic known as the Spanish Flu. San Juan Island was no exception.

First, there are some things to know about the Influenza of 1918.

It did not originate in Spain. It’s just that Spain, as a neutral country in World War I, had no reason to suppress news of its spread while other countries did, so as to avoid showing any weakness to their war opponents. This created an impression that the flu had originated there.

It lasted longer than 1918. Its run was almost two years, ending in 1920. The pandemic caused by this particular influenza hit Washington state hard in the fall of 1918. With so many servicemen from around the country housed in military camps, or returning from the war, this deadly strain of influenza spread quickly and could develop into bacterial pneumonia, the more serious threat to life. This global pandemic would kill an estimated 50 million people around the world, and about 675,000 in the U.S., including about 6,500 residents of Washington state. This was no garden variety flu bug.

It didn’t entirely go away. Since 1918, nearly all cases of Type A influenza have had roots in the more deadly Spanish Flu.

Friday Harbor’s first pandemic picture:

Influenza roared into the state in early October of 1918, peaking in Seattle later that month. Then it came to the San Juans. And it stayed for about six unwelcome months. The island caught the end of what became known as the first wave of infection and then, as preventative restrictions loosened, a second wave hit and caused more local illness and death.

At one point, Washington State Health Commissioner Dr. Thomas D. Tuttle sent a telegram to the U.S. Surgeon General, asking for quarantine recommendations as to length of time. The response: “The Service does not recommend quarantine against influenza.” Knowing that he did not have the federal government’s support, Dr. Tuttle requested that counties maintain their own voluntary six-week quarantine periods. He asked that schools, movie theaters, pool halls, churches, and businesses wherever possible close for the duration of the quarantine period.

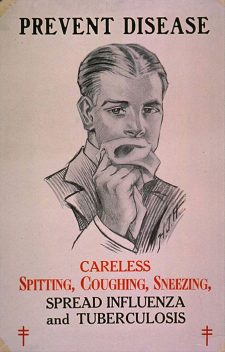

So how was community health news disseminated in the islands? Posters on storefronts or at the courthouse? As today, these were popular methods to spread the word on community topics. Town Council meeting minutes kept to an appropriate focus on a sewer system, public services, and expenses. Health news coming from the County Council, does not appear to have been as prominently published as it is today. Their news generally had to do with road maintenance, taxation, appointments, or general business matters.

Although not a lot of detail was included in local newspapers at the time, we do know that schools on San Juan Island closed for a number of weeks. For the most part, public gatherings were not allowed (with a few notable exceptions, such as welcoming soldiers returning home from the war and an impromptu parade in Friday Harbor following the first Armistice Day).

Prevention measures were voluntary, inconsistent, and often ineffective. It was believed that fresh air and healthy living could ward off the virus. It didn’t. The wearing of face masks was done by many people, on a voluntary basis or at the request of local government. The only statewide preventative regulation was issued by Dr. Tuttle on November 3, 1918. It required that six-layer surgical gauze masks covering nose and mouth be worn in public places, such as restaurants and stores, and that businesses keep doors and windows open for ventilation. Dr. Tuttle lifted the statewide order for the wearing of face masks in public after Armistice Day, just several days later, in part because many people had stopped doing it anyway. Predictably, the state experienced a surge of influenza cases when more people gathered in larger groups and for winter holidays, without masks. Health officials were left with one last effort. Those with influenza or exposed to it were ordered to stay home.

It is hard to say how many people died from the Spanish Flu on San Juan Island or throughout the county. It does not appear that the Washington State Board of Health ever issued reports on infection rates or mortalities by county. There was very little coordination between the state board and mostly part-time local health officials in communities. Funding and staff just were not in place to do what needed to be done. Local obituaries in the Friday Harbor Journal rarely mentioned influenza as a cause of death. One wonders if the omission was for family privacy, so as to avoid being labeled as “the contagious ones.” Death certificates are helpful for historical research, although not all from this period are accessible.

In 1918, San Juan County had a population of just around 3,600. Our small county was home to 124 men who left families behind to serve our country in World War I, the “Great War” as it was called then. The Spanish Flu took the lives of two of these men, George D. Allain and Walter E. Heidenreich. You can see their names on the stone monument in Friday Harbor’s Memorial Park, a project of the Women’s Study Club, dedicated on November 11, 1921.

Here are some of the people from San Juan Island who became victims of the influenza pandemic:

George D. Allain, 21. U.S. Navy. Died October 2,1918 at the University of Washington Hospital in Seattle. George was the hospital’s first fatality of the pandemic. He was the husband of Josephine McKay, a granddaughter of San Juan Island pioneer Charles McKay. A son named Laurence was born to Josephine two months after her husband’s death and one day after her grandfather McKay’s death.

Walter E. Heidenreich, 24. U.S. Navy. Died October 8, 1918 at Naval Training Camp in Seattle, a month after entering the service. He was the son of George and Marguerite Beck Heidenreich.

Frances Thomas Bellevue, 21. Died Nov 15, 1918. She was the wife of Ernest Bellevue and mother of their three young children ages 3, 2, and 2 days. The family had recently moved to Anacortes from Friday Harbor. After Frances died, the children were raised by grandparents, while Ernest went to work in Oregon lumber camps. The two sons, Ralph and Robert, went to live in Seattle with their maternal grandmother Lena Thomas. Mildred, the newborn baby girl, was taken in by her paternal grandmother on San Juan Island, Harriett Wotton and second husband Rudolph H. Rosler. Mildred was raised on the island, married Joe Jasper, and died here in 2002.

Norman E. Churchill, Sr., 66. Died January 17, 1919. He was the husband of Sarah Jane McKay (aunt of Josephine McKay Allain) and father of four adult children.

George A. Nicholson, 39. Died March 12, 1919. He was the first husband of Lettie Carter (who later married William Roark) and father of five-year-old Marjorie.

Harold Butterworth, 19. U.S. Navy. Died November 30, 1917 at the Naval Hospital in Brooklyn, New York. He was the son of Levi and Mary Brierley Butterworth.

Although Harold Butterworth’s illness and death occurred before the initial outbreak of the pandemic in the U.S., it should be noted that he was the first from San Juan County to die in service to the country during World War I and he did succumb to pneumonia.

In 1918, as today, the San Juan Islands were somewhat more protected from contagion than their neighbor counties on the mainland. Just as today’s Covid-19 pandemic is influencing and changing the definitions of normal social behavior, at least temporarily, there are many parallels with our community’s experience during its first pandemic. And the wearing of face masks was a hot topic in 1918-1919, just as it is today. Yes, we have been here before.

Do you have a family story to tell from San Juan Island’s first influenza pandemic? Please do share with the San Juan Historical Museum.

You can support the San Juan Update by doing business with our loyal advertisers, and by making a one-time contribution or a recurring donation.

Categories: Health & Wellness, History

No comments yet. Be the first!

By submitting a comment you grant the San Juan Update a perpetual license to reproduce your words and name/web site in attribution. Inappropriate, irrelevant and contentious comments may not be published at an admin's discretion. Your email is used for verification purposes only, it will never be shared.