Freezer Burned: Snowshoe Hares

Posted December 4, 2020 at 5:30 am by Hayley Day

“FREEZER BURNED: Tales of Interior Alaska” is a regular column on the San Juan Update.

By Steve Ulvi, San Juan Island

Just how much difference can a few bunnies make?

Just how much difference can a few bunnies make?

Common notions when hearing of the place called Alaska, are a mish-mash of life experiences (or lack thereof), bookish knowledge and an active imagination. That place name has represented a dreamscape for people the world over thanks to the incredible popularity and widely translated prosaic tales of daring-do from Robert Service and Jack London. There were no photos and few drawings. Programs about Alaska using the incredible lenses of drones and modern cameras blow our minds but often underachieve with simplistic narration and silly wildlife sequence music.

Panoramic images flood and excite the brain far more than words. In my view, nearly all of the proliferation of so-called reality TV shows set in the north, play fast and loose with common preconceptions but invariably become farcical with production artifice to maintain ratings.

Admittedly, “Sergeant Preston of the Yukon” impregnated my imagination from a small black and white TV (and radio show) in the late 1950s, yet was as predictable and simplistic as any adventure show could possibly be. Even by that era’s standards.

A person cannot predict how the worm of imagination will turn in that part of the brain where wanderlust and vision quest are nurtured.

Today’s spectacular advances in science and technology shed light on old mysteries of the north, but more often open exciting new threads of inquiry connecting the dots in the web of northerly enigmas.

Clues to Alaska mysteries patiently await scientific advances locked in rocks, ice, ancient lake sediments, permafrost or fossilized bones and reveal stories far more intriguing than fiction. Alaska itself is a jumbled, tortured mess of rock from elsewhere welded to the margins of the North American plate. At least 12 species of dinosaurs endured dark snowy winters in mixed broad leaf and coniferous forests on Alaska’s North Slope for millions of years. DNA sequencing has provided insights and indisputable proof of relationships that were pure speculation a few decades ago (e.g. grizzly bears and polar bears can interbreed as the great white bears certainly evolved from ice wandering grizzlies not so long ago).

The most fascinating “Big Story” for me is of the post-glacial land connection, the 300-mile wide Bering Land Bridge, slowly exposed to sunlight and air, vegetated over thousands of years, that drew waves of wildlife and northern peoples from the Old World into a vast unpeopled continent. From an early age, I was awestruck with the artistic renderings of the extinct mammals of the Pleistocene, reading fictional and informational books about excavations at the La Brea Tarpits. I also thumbed through National Geographic articles of the wild perusing more than the photos of bare breasts in the tropics.

The most fascinating “Big Story” for me is of the post-glacial land connection, the 300-mile wide Bering Land Bridge, slowly exposed to sunlight and air, vegetated over thousands of years, that drew waves of wildlife and northern peoples from the Old World into a vast unpeopled continent. From an early age, I was awestruck with the artistic renderings of the extinct mammals of the Pleistocene, reading fictional and informational books about excavations at the La Brea Tarpits. I also thumbed through National Geographic articles of the wild perusing more than the photos of bare breasts in the tropics.

In those first few years out on the Yukon River in the 1970s, the most mind-boggling thing was the over the horizon size of even our little neck of the woods. But the steepest learning curve was predictable as we were not experienced hunters nor practiced in butchering and preserving food off the grid. The uneven distribution and fluctuating seasonal availability of animal flesh in a winter-dominated climate was a real dope slap for me. Being hard-up against the border with Canada didn’t help. Biomass of harvestable animals, fish or fowl in the expanses of the subarctic can vary from scarcity to richness from week to week, season to season, year in year out.

What we couldn’t have known as we began our decade of living at Windy Corner was that enhanced aerial monitoring, habitat studies and statistical modeling was revealing that the nearby Forty Mile Caribou Herd had dwindled to about 5,500 animals from an estimated high of 450,000 in the 1920s. Area moose numbers had declined to some of the lowest in the entire State to about one moose, or less, per 4 square miles. (For reference, that would roughly equate to 10 moose in a decent habitat area the size of San Juan Island).

To complicate things, there had been a decline (and aging) in the local human population of historic Eagle City and the nearby Han Athapaskan village, which translated to a diminution in the traditional expanse and efforts in trapping, denning and shooting wolves and hunting bears. State game laws had long prohibited the use of strychnine baits but federal wildlife control agents used it along with aerial gunning in focused wolf control efforts to pump up moose and caribou in the area until statehood dawned in 1960).

The gap between my youthful temperate zone backpacker/angler expectations and subarctic hunter realities was at first stunning. Gill netting some late run chum salmon and looking for small game while hoping for the chance at a large animal (with only one rifle) was the natural course of things right off the bat. By the time the cabin was roofed and holding heat, black bears were denning, waterfowl gone, fish icing-in. I remember thinking “where the heck are the snowshoe hares and grouse” as the trackless snow began to accumulate in October.

We didn’t know that the highly variable snowshoe hare (also appropriately called Varying Hare) population was just emerging from the cellar of scarcity, the bottom of a variable 8 to 11-year cycle. Since our area was not endowed with swaths of quickly regenerating willows, as were disturbed riverine areas with large islands and sloughs, or revegetating wildfire burns, we saw very few “rabbits” or tracks. Ditto for the ghostly lynx and traipsing red fox. ‘Hungry country’ makes for a steep learning curve and eating a lot of dried pinto beans. Our “jump off” into the wild along the iconic Yukon River was made more difficult by a complex ecological synchronicity well beyond our newcomer understanding.

Obviously, indigenous tribes across the subarctic long knew that hares and some predators erupted then crashed in a roughly predictable way over 10 winters or so. Certainly, this particular element of deep traditional knowledge was tied to the cause and effect relationships between creation stories, human behavior and the powerful spirits of all the beings of the boreal forest. It is known that people living hard in the cold cannot survive, but in fact will eventually weaken and starve, when subsisting primarily on abundant hares; dark, protein-rich meat devoid of essential fat calories.

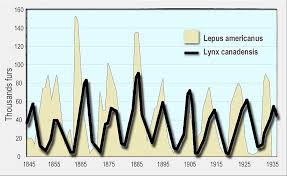

The snowshoe hare is a different sort of ‘keystone species’ because they energize massive waves of increased biomass across the subarctic in North America. The most extreme amplitude in highs and lows happen in the farther north regions. Strangely, the waves of eruption seem to spread from Saskatchewan, like a vast flood tide, arriving with a delay of a couple years in Alaska. Hudson’s Bay Company record-keeping of fur catches over nearly 200 years clearly illustrated the cyclic spike and crash of hares, whose pelts were also sold along with far more valuable lynx pelts. This relationship was not lost on early biologists craving data.

The snowshoe hare is a different sort of ‘keystone species’ because they energize massive waves of increased biomass across the subarctic in North America. The most extreme amplitude in highs and lows happen in the farther north regions. Strangely, the waves of eruption seem to spread from Saskatchewan, like a vast flood tide, arriving with a delay of a couple years in Alaska. Hudson’s Bay Company record-keeping of fur catches over nearly 200 years clearly illustrated the cyclic spike and crash of hares, whose pelts were also sold along with far more valuable lynx pelts. This relationship was not lost on early biologists craving data.

Female hares begin to breed after their first winter. Gestation is just over a month long. A healthy doe may have 3 to 4 litters averaging 5 young “leverets” over a summer, or about 16 to 18 offspring per summer! Hares are born fully furred, eyes open and hopping within a couple of days. They cluster quietly in heavy cover in a day bed, then at night use the same routes to good feed areas. The best winter habitat and browse areas serve as scattered “refugia” from which re-population spreads (not all regions are exactly in sync) after the numerous predators migrate away or succumb to starvation. A greater percentage of young hares make it through the winter to breed. The fuse for the eventual explosion of bunny biomass is lit. Local populations can increase from less than one hare per acre to 6 to 8 and can easily exceed the weight of moose inhabiting the same area.

After the fuse has burned hotly for a couple of years the various predators return through in-migration and their own increased clutches of eggs or litters born as their own reproductive nutrition improves and a greater percentage of their offspring are able to survive the test of winter. Predator populations steadily increase for a few years and trapper’s catches of lynx, red fox, coyote and even marten can increase greatly until the crash. But it is the Snowshoe Hare-Canadian Lynx population synchronicity that stands alone as a predator-dependent marvel in wildlife ecology.

After the fuse has burned hotly for a couple of years the various predators return through in-migration and their own increased clutches of eggs or litters born as their own reproductive nutrition improves and a greater percentage of their offspring are able to survive the test of winter. Predator populations steadily increase for a few years and trapper’s catches of lynx, red fox, coyote and even marten can increase greatly until the crash. But it is the Snowshoe Hare-Canadian Lynx population synchronicity that stands alone as a predator-dependent marvel in wildlife ecology.

But just as hares “breed like bunnies” they can also suffer mightily from physiological stress. Just the constant presence and chases by expanding numbers of lynx and other eaters of hares in the summer cause their birthrate to decrease. Even red squirrels, ermine and small owls can kill the young hares in summer. Interestingly, maternal stress is passed on to the young. A cornucopia of green foods abounds in summer but the terminal twigs and buds of woody shrubs and trees like paper birch, poplar and willows (and eventually their bark) are winter staples. These plants have evolved to produce certain compounds to reduce munching that can disrupt hare digestion and even cellular energy transport. The twigs higher in the trees do not contain the toxins.

A couple of years later we were much better equipped and steadily gaining knowledge in a cold school of hard knocks. Nice to have a pot to piss in earning some wages in town during the summer. We learned hare snaring from our sister-in-law in the village, a hard-working and hard-living Han Athapaskan woman who was adept at a woman’s traditional skills. Braided picture wire with a sliding loop, and about 2 feet of extra wire was tied to shrubs on a regularly used feed trail that intersected our woods trails. As with all snares, sticks were poked into the snow to guide the head into a 5-inch loop a few inches off the snow.

As the hare numbers increased steadily and either because of poor moose hunting luck or temporarily relocating our family to a distant area for early winter trapping, we modified the technique some and shared in snare line duties near our home base. We cut dry 3-foot sticks and attached the picture wire loops ahead of time along with baling wire tie-downs. Easy to stick in a daypack like arrows in a quiver to quickly make new sets. We could easily carry in several dead hares with the sticks over a shoulder. We quickly realized that felling birch for firewood created a feed pile of toxin-free twigs around which we concentrated our snares.

First-year hares were a bit smaller and more tender while mature bunnies attained 3-4 pounds. Two cut up and fried in a big cast-iron skillet of rendered fat with hearts and livers was a good meal. Tularemia was supposedly a potential problem but we examined livers and if splotched they were tossed and the meat always cooked medium-well. I have never worn gloves to butcher anything including rabbits. If we had moose or caribou in the larder we usually held off on snaring bunnies.

Early winter hares were best but by late winter they were eating more bark and conifer needles (if the snowpack was deep enough) and became much more gamey. No winter hare of the hundreds we harvested ever had a scintilla of fat. Hides were not sold due to the bother and scant price but were sometimes dried and used in our native-style footgear. Other people made rabbit skin blankets and winter socks.

The eventual abundance of bunnies energized us and the entire boreal forest ecosystem. My interest in raptors was greatly rewarded with hearing and seeing many great horned owls, goshawks and hawk owls. Trapping lynx improved, but of course, pelt prices dropped (from $350 down to less than $100) with the increasing market glut of pelts. We enjoyed eating lynx hindquarters as a sweet treat meat. Red fox and marten were dependent upon small rodents but also increased with the bunny explosion. Wolves did not seem capable of catching a healthy zig-zagging hare except in the open.

In odd years with late or patchy snowfall, we benefited from .22 hunting the stark white bunnies against a dark background. Continuing climate change is causing belated first snow and earlier melt in spring working natural selection against bunnies that turn white earlier, especially in the southern boreal forest. Winter rain showers and thaws, once very rare, but more common now can create a crust on the snowpack that generally benefits the scampering hares. To a point.

After the crash lynx were abundant, easier to catch and more often seen but then either migrated (radio collar studies revealed treks of nearly 1,000 miles) or starved. I found lynx curled up on our trails, skin and bones, starved to death, especially during the stress of deep cold spells of minus 50F or lower. Sadly, for me woods that had been so full of life and interaction for us, would again be quiet for a few years. An ancient and profoundly impactful ecological cycle was to begin anew. In an odd way, it has to be one of the most amazing cyclic wildlife spectacles on the planet.

After the crash lynx were abundant, easier to catch and more often seen but then either migrated (radio collar studies revealed treks of nearly 1,000 miles) or starved. I found lynx curled up on our trails, skin and bones, starved to death, especially during the stress of deep cold spells of minus 50F or lower. Sadly, for me woods that had been so full of life and interaction for us, would again be quiet for a few years. An ancient and profoundly impactful ecological cycle was to begin anew. In an odd way, it has to be one of the most amazing cyclic wildlife spectacles on the planet.

You can support the San Juan Update by doing business with our loyal advertisers, and by making a one-time contribution or a recurring donation.

Categories: Freezer Burned

No comments yet. Be the first!

By submitting a comment you grant the San Juan Update a perpetual license to reproduce your words and name/web site in attribution. Inappropriate, irrelevant and contentious comments may not be published at an admin's discretion. Your email is used for verification purposes only, it will never be shared.