The Wreck of the SS Clallam

Posted January 3, 2018 at 5:49 am by Tim Dustrude

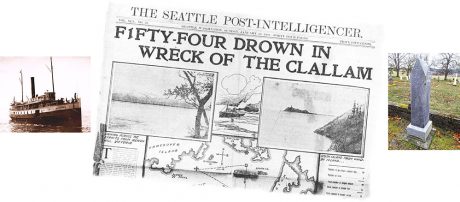

Photos: SS Clallam, Courtesy UW Special Collections; Front page story, January 10, 1904, Courtesy Seattle Post-Intelligencer; Dellie LaPlante Sullins monument, Valley Cemetery, San Juan Island – Click to enlarge

It’s time for the Historical Museum’s monthly History Column…

A clairvoyant bell sheep and a gale most foul: The Wreck of the SS Clallam

A benefit of writing about local history is that we can tell a story in the context of our own place and our own people. What was once international news, recounted in newspapers from Victoria to New York City, is still today a local San Juan Islands story known as The Wreck of the Clallam. It began on January 8, 1904 when the excursion steamer SS Clallam met its fate in the Strait of Juan de Fuca during a rising gale, with a loss of 56 lives. Of these, eight were from San Juan and Orcas Islands. Four more islanders would be saved and counted among the thirty-six passengers and crew who lived long enough to be rescued from drowning. We remember their names.

Drowned: Ulysses Grant Hicks, San Juan Island; Members of the LaPlante family of San Juan Island and Orcas Island – Peter LaPlante, Caroline King LaPlante and daughter Verna, Dellie LaPlante Sullins and her children Leonard, Lewis, and Violet

Rescued: William King (brother of Caroline LaPlante), William LaPlante (husband of Caroline LaPlante), Thomas Sullins (husband of Dellie Sullins), and John Sweeney

All of these islanders were on their way to the Vancouver Island mining operation of Thomas Sullins. The Sullins family had recently moved from Orcas Island, returning to the islands for a visit with family and friends over the Christmas holiday. Joining them was Robert Miller of Orcas Island, completing the group of thirteen. That unlucky number was not the first of this story’s bad omens.

The SS Clallam was a 168 foot, wood-hulled steamship and the pride of the Puget Sound Navigation Company when launched just months earlier in 1903. Superstitious sailors considered it a cursed ship. On launch day, Old Glory flew upside down in an unintended distress signal, and the champagne christening didn’t happen when the bottle missed the ship. Then on that fateful morning of January 8, 1904 as livestock was about to be loaded onboard in Seattle, an experienced bell sheep balked for the first time and refused to lead the herd onto the ship. No coaxing was successful and he was left behind on the dock. What did the bell sheep know?

The Clallam departed Seattle and headed toward Port Townsend. The group of thirteen from the San Juans had arrived at Port Townsend earlier to pick up the steamer for the last leg of the run to Victoria. Unexpectedly, Robert Miller changed plans in Port Townsend and sailed to Seattle instead. It saved his life. The islands group of twelve boarded the Clallam and it headed out in stormy seas – and into a rising gale. There were now 92 people onboard.

Bounced about in the raging Strait of Juan de Fuca, the ship soon began to take on water through a broken porthole. Coal bunkers flooded, compromising bilge pumps. As the ship began to founder, three lifeboats were launched for all women and children aboard, plus some of the men. All were drowned within minutes as the unrelenting sea swallowed the lifeboats, one by one. Particularly heartbreaking moments were when sisters-in-law Dellie Sullins and Caroline LaPlante, along with their children, were lost while holding their youngest babes above the waves as long as they could. Caroline’s brother William King was the last man to leave the ship after the midnight hour when 36 survivors were rescued by tugboats. As King looked back upon the sinking steamer, he lamented how “phosphorescence on the water cast a ghostly light over the scene.”

The wreck of the Clallam is thought to be the worst maritime disaster in the Salish Sea. To read more about this event, the Coroner’s Inquest, the manslaughter charges and other details of this tragedy, there is an article on History Link, Washington state’s online encyclopedia. Find out more about local island history on the San Juan Historical Society and Museum’s website at www.sjmuseum.org.

You can support the San Juan Update by doing business with our loyal advertisers, and by making a one-time contribution or a recurring donation.

Categories: History

No comments yet. Be the first!

By submitting a comment you grant the San Juan Update a perpetual license to reproduce your words and name/web site in attribution. Inappropriate, irrelevant and contentious comments may not be published at an admin's discretion. Your email is used for verification purposes only, it will never be shared.